10 women of San Sebastian that you should know

This is not the first time we have talked about women of San Sebastian in this blog, as we have written about Juanita Larando and Catalina de Erauso on previous occasions.

But in Donosti there are many more women worthy of mention, some of them are hardly known and others could be written about in books, and all of them are important in their own way.

That is why we have decided to compile 10 of them and pay them a small tribute, which we have divided into two parts. So without further ado, here are 10 women of San Sebastian that you should know.

Gracia de Olazabal

Best known for being the wife of Alonso de Idiaquez, who was secretary to Charles V, their marriage served to strengthen the Olazabal family’s power in Donosti and for Alonso to obtain the necessary wealth to control San Sebastian and Gipuzkoa, that is, she was the wealthy and the Donostian, in fact, the Idiaquez family palace that formerly stood in Calle Mayor and which disappeared in the fire of 1813 was built on plots of land provided by Gracia as part of her dowry.

In 1539 the couple founded the convent of San Telmo, now a museum, where they are buried, and ordered the refoundation of the Dominican convent of San Sebastián el Antiguo in 1546 (from where, years later, Catalina de Erauso fled). Gracia also had full responsibility for the couple’s estate, even before Alonso’s death in 1547. A good example of this is that it was she who signed the contracts for the construction of the palace in 1546.

Sepulchre of Gracia de Olazabal and her husband Alonso de Idiaquez in the church of San Telmo. Photo from Wikipedia.

Francisca de Aculodi

Although the title of first female journalist in history belongs to Elizabeth Mallet (who in 1702 founded the Daily Courant newspaper in London), the truth is that Francisca de Aculodi published the journal Noticias Principales y Verdaderas (Top and True News) a little earlier, in 1687. This was possible because her husband, Martín de Huarte, bequeathed her the title of “printer of the very noble and very loyal province of Guipúzcoa” on the condition that she would run the printing press he owned in Donosti until her children were older and could take over the business. And she did so while maintaining her husband’s conditions and salary, which was unusual at the time.

She published Noticias Principales y Verdaderas, a fortnightly magazine, a translation of a newspaper published in Brussels in French, to which she added local news that she wrote herself. Her signature can be seen during the first two years of the journal, although it continued to be published until 1698.

Today Francisca de Aculodi gives her name to the prizes awarded by the University of the Basque Country for the inclusion of the gender perspective in end-of-degree projects.

Cristina Brunetti

There is not much information about Maria Cristina Fernanda Brunetti Gayoso de los Cobos, Duchess of Mandas and Villanueva, but her name will live on forever in Donosti thanks to the park and palace of Cristina Enea located in the Egia neighbourhood. Of Italian origin and married to Fermín Lasala y Collado, who became Duke of Mandas, their marriage may give the impression of having been for reasons of interest (she had noble titles and he had a large fortune), but in reality they must have loved each other sincerely and she also came from a wealthy family, overturning any possible prejudices.

Cristina accompanied her husband on his diplomatic career in Paris (1890-1892/1895-1897) and London (1900-1905), where they not only attended elegant parties, but also had to navigate in a complicated political environment that already hinted at the First World War. The couple were also responsible for the marriage of Alfonso XIII and Victoria Eugenia, in an attempt to bring the Spanish and British monarchies closer together and to strengthen Spain’s role in a period when its power was waning.

If you want to know more about Cristina, Fermín and the historical context in which they lived, the Cristina Enea Foundation published in 2021 (Breve) Vida de la Duquesa de Mandas ((Brief) Life of the Duchess of Mandas) written by the historian Carlos Rilova Jericó, which you can read here in Spanish.

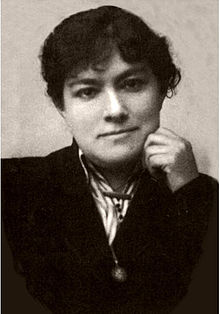

Portrait of Cristina Brunetti, Duchess of Mandas.

Micaela Elizaran

Very little is also known about Micaela Elizaran, who was from Tolosa and owned several plots of land in Donosti. It is also known that she was widowed young and that she lost her daughters too soon. That is why, finding herself alone and with money, she decided to use her wealth to help the poor children of San Sebastian. Thus, in 1911 she founded the Los Ángeles school in San Juan Street and the San Miguel Arcángel school next to Santa María del Coro in 1918, the former for boys and the latter for girls. For decades, children from disadvantaged families in San Sebastian were able to attend these schools free of charge, receiving a good education that would help them to find a good job in the future.

It also ceded the building at Fermín Calbetón 19 to be used as a care centre for the elderly, which it still is today, as well as a care centre for people with physical and/or intellectual disabilities.

The Los Ángeles school no longer exists and its building now houses the headquarters of the Orfeón Donostiarra. The San Miguel Arcángel school, which was never called that, as it was always known as Escuelas Elizaran, continues to function as an educational centre, although it now offers vocational training degrees under the name of Elizaran Ikastetxea.

Micaela Elizaran

Nicolasa Pradera

Nicolasa Pradera

Before Arzak, nouvelle Basque cuisine and the many Michelin stars in Donosti, Nicolasa Pradera put San Sebastian on the world gastronomic map with her restaurant Casa Nicolasa, opened in Aldamar Street in 1912. Originally from Markina, she came to Donosti to work as a kitchen assistant for a wealthy family and soon became the main cook.

After getting married, she opened the restaurant, which was a great success in that Donosti frequented by the elite and where economic and political meetings that would mark the future of Spain took place. In 1930 Nicolasa sold the restaurant to her former assistant, María Urrestarazu, and two years later she opened the restaurant Andía with her daughters in the heart of La Concha promenade. After the Civil War she arrived in Madrid and with one of her daughters opened another restaurant, Nicolasa, where she also enjoyed great success.

Today both restaurants no longer exist, and in the place of the one in Donosti is the pension of the same name, but Nicolasa’s name continues to survive thanks to the recipe book she wrote in 1933, encouraged by Gregorio Marañón, who wrote the prologue to it. This book, La Cocina de Nicolasa (Nicolasa’s Kitchen), is a bestseller and has now gone through 21 editions. It contains recipes from traditional Basque cuisine, the same cuisine she served in her restaurants.

Benita Asas

Benita Asas was born in Donosti, although she spent most of her life in Madrid and Bilbao. She studied to be a teacher in Valladolid and after graduating she moved to the Biscayan capital, where she worked as a teacher until 1902, when she asked to move to Madrid. It was in Madrid that Benita began to write textbooks, but also articles on feminism, the suffragette movement, the need to educate women and equal rights for men and women.

In 1913 she founded the fortnightly magazine El Pensamiento Femenino (The Femenine Thought), whose editorial board consisted only of women. And in 1918, together with other feminist women of the time, she formed part of the first board of directors of the National Association of Spanish Women (ANME), of which she was president from 1924 to 1932. This association was the most important feminist organisation in Spain, and Clara Campoamor, María de Maeztu and Victoria Kent, among others, soon became prominent in it, and Benita was a regular contributor to its publication Mundo Femenino (Femenine World).

Although, after much effort, women’s suffrage was finally recognised during the Second Republic, the Civil War destroyed all the work they had done. Benita spent the whole of the war in Madrid and once it was over she applied for re-entry into the teaching profession. Her feminist and anti-clerical past was given as an excuse to disqualify her in 1940 for management and positions of trust. However, Benita was already 66 years old and retired shortly afterwards, moving to Bilbao, where she died at the age of 95, totally forgotten and made invisible until her figure has recently been vindicated by the feminist movement. In fact, María José Villa Rodríguez wrote in 2019 her doctoral thesis Benita Asas Manterola y los feminismos en España (1873-1968) (Benita Asas Manterola and feminisms in Spain (1873-1968)) which you can read here in Spanish.

Benita Asas

Ignacia Zabalo

The history of women is a history of anonymity and pseudonyms in order to be published or to avoid persecution. Of works attributed to men, sometimes unknown, sometimes already reputed authors. This is the case of Ignacia Zabalo, whose work until relatively recently was believed to have been created by her brother, Txiki Zabalo. Both were cartoonists and illustrators, although Ignacia always signed her work as Nor-Nahi (anyone), which led people to think that it was just a pseudonym for her better-known brother. But although the style of the two was similar, Ignacia’s is more elegant, more decorative.

Ignacia was born in Donosti in 1905 and began working with her brother at the age of 20, for the Argia calendar and for Agere, a magazine for girls in which she did almost all the work: mastheads, lettering, ornamentation, drawings, jokes, comics… Ignacia can therefore be said to be the first professional woman cartoonist in the Basque Country in the 20th century. But Ignacia, seeking a life independent of her brother, moved to Barcelona in 1931. There, eight years later, at the end of the Civil War, a bomb dropped in the doorway of her house put an end to what would almost certainly have been a successful professional career.

Blanca Brisac

The Civil War also ended the life of Blanca Brisac, one of the Thirteen Roses. Blanca was born in Donosti and later moved with her family to Madrid, where she worked as a pianist in the music band of the Sala Alcalá, which screened silent films. Here she met her husband, Enrique García Mazas, with whom she had two children, Mercedes, who died of pneumonia a few months after her birth, and Enrique. After they married, she worked as a seamstress at home and he as a violinist in a café.

They led a quiet life until 3 May 1939, when they were accused of holding clandestine meetings at their home in which they were preparing an attempt on Franco’s life. Blanca was imprisoned on the 24th of that month, aged just 29, accused of an attempted plot against the dictator and of being implicated in the murder of the Civil Guard commander Isaac Gabaldón, his daughter and his chauffeur. Although the accusation of the assassination attempt was finally rejected, Blanca and Enrique were condemned to death for belonging to the Unified Socialist Youth. Thus, on 5 August 1939, within hours of each other, they were shot along with 43 other men and the rest of the Thirteen Roses.

Blanca Brisac

María Dolores Goya

María Dolores Goya

When people talk about the clandestine ikastolas of the Franco dictatorship, they always talk about Elbira Zipitria, but, without detracting from Elbira, there were more Andereños who risked their lives to teach Basque in the underground. One of them was María Dolores Goya, whose ikastola in Carquizano Street in Gros operated from 1951 to 1975, the last five years under the direction of her daughter Miren Egaña.

María Dolores studied to be a teacher and passed the competitive examination in 1936. The entry of the requetés into Donosti cut short her plans and she had to flee with her family to Bermeo by boat. In Bizkaia he got a job in a school in Plentzia, where she stayed until the bombing of Gernika forced the closure of all educational centres. After that, she left for the United Kingdom on the ship La Habana, one of the many ships chartered by the Basque Government to send Basque children away from the war, along with 95 other leaders and 3500 children. On arrival in Southampton, Maria Dolores was sent to the Isle of Wight, where she stayed for 7 months. She then travelled to Paris, together with her sister, who worked for the Basque Government in exile. There she spent 2 years teaching Spanish to the children of a Polish family. From Paris she moved to Saint-Jean-de-Luz, with her parents and another sister. Finally in 1941 she was able to return to Donosti, although she was almost arrested at the border for having fled with the children to the United Kingdom.

Two years later she opened a school in Ergobia and got married. After her second child, she had to give up her job, and after the third, the family moved to Gros, to Carquizano Street, where in 1951 she opened her ikastola, encouraged by the also teacher Elixabete Maiztegi. In this ikastola, as in Elbira’s, the classes were in Basque, with books such as Xabiertxo (Little Xabier) (illustrated by the aforementioned Txiki Zabalo), although there was a substantial difference: in María Dolores’ ikastola there were tables and chairs. The ikastola had as many as 80 pupils and, in addition to the classes, they organised Christmas activities, or all the families would meet up in Plaza Cataluña to play in Basque. In a way, the María Dolores ikastola functioned like the cooperative ikastolas that can be found all over the Basque Country today.

Casilda Hernáez

Soledad Casilda Hernáez was born in the Fraisoro cradle house in Zizurkil, to a single mother and unknown father, although she grew up in the San Sebastian neighbourhood of Egia, where she learnt to read and write at the Atotxa public school. In 1931 she joined the Libertarian Youth, attending the libertarian athenaeums, which would become her second school. At a very young age she was arrested for calling for a strike in a company staffed by women. Her habit of nudism in La Zurriola was also scandalous. And in 1934, during the 1934 Revolution, she was arrested again and sentenced to 29 years in prison, 9 for distributing propaganda and 20 for possession of explosives. Fortunately for Kaxilda, as she was known, she only served two years thanks to the general amnesty of the Popular Front of 1936. Soon after, she met Félix Liquiniano, who was to become her lifelong companion.

When the Civil War broke out, she took part in the defence of Donosti, and then went to Irun, the Aragon front and the Ebro front, and once the war was over she went into exile with Félix in France, where they were in the Argelès and Gurs concentration camps. In 1940 they were released and in 1943 they settled in Biarritz. Here their home served as a centre of anti-German and anti-Francoist operations, and when the anarchist movement lost strength, they showed solidarity with the recently created Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA, whose logo Félix himself designed). Soon his relationship with Félix broke down, which led to a period of depression from which she managed to emerge some time later.

Kaxilda died in 1992 of cancer after a lifetime of anarcho-syndicalist, feminist and anti-Francoist fight and is now buried in Biarritz next to Félix. If you are interested in knowing more about her, in 1985 the book Casilda, miliciana: historia de un sentimiento (Casilda, militiawoman: the story of a feeling) was published in Spanish by Luis María Jiménez de Aberásturi, who interviewed her during her lifetime, and in 2022 both the documentary Casilda, el eco de otros pasos (Casilda, the echo of other steps) by Juan Felipe and the comic Casilda revolucionaria (Revolutionary Casilda) by Rubén Uceda Villanueva were published for now only in Spanish.

Casilda Hernáez, aka Kaxilda.